Blog

Rum history

Part 2: The Colonial SpiritPart 3: The Latin LegacyPart 4: Rum without bordersPart 5: The story of Coca-ColaThe History of Rum, Part I: The Origins of Rum – Sugar, Slavery & Spirit

Part I of a Trilogy:

- The History of Rum in General and Development

- The Colonial Spirit: Rum in the English-Speaking World

- Rum and Revolution: French, Spanish & Portuguese Contributions

Rum’s history is inextricably linked to the great tides of global exploration, colonization, slavery, and trade. While today it’s seen as a tropical indulgence, its origins are rooted in some of the most transformative and turbulent chapters of human history. Before we explore how rum shaped the colonial and revolutionary worlds in later parts of this series, we begin here: with the birth of rum itself, and the sweeping story of sugar, slavery, and spirit.

From Grass to Gold: The Global Journey of Sugarcane

Sugarcane, a towering tropical grass, originated in Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. As early as 500 BCE, people in India had learned to extract and crystallize sugar. The knowledge moved westward via trade and conquest, and by the 7th century, Arab traders had introduced sugar cultivation to Persia and North Africa. As Europe emerged from the medieval period, returning Crusaders developed a taste for the sweet substance — and a hunger for more.

Sugarcane was later brought to the Iberian-controlled islands of Madeira and the Canaries, where plantation agriculture first took root in the 15th century. These islands became crucial testing grounds for the model of intensive sugar cultivation that would soon be exported across the Atlantic.

Columbus, Conquest & Cane

In 1493, on his second voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus brought sugarcane cuttings from the Canary Islands to Hispaniola (modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic). The Caribbean’s hot, humid climate and rich volcanic soils proved ideal for growing cane. What followed was an explosive expansion of sugar production across the region — and the beginning of what some would call the “Sugar Revolution.”

By the 16th century, European nations realized the potential of sugar as a luxury export. The Caribbean soon transformed into a network of plantations, powered by the brutal labour of enslaved Africans forcibly transported via the transatlantic slave trade.

Molasses and the Invention of Rum

Sugar refining produces a thick, dark syrup as a byproduct: molasses. Initially discarded or fed to animals, molasses began to ferment naturally in the heat of the tropics. Enslaved workers and colonists soon discovered that this fermented substance could be distilled into a potent, intoxicating drink.

By the early 17th century, rum distillation had taken hold in sugar-producing colonies like Barbados and Martinique. The earliest recorded terms for this rough spirit included “kill-devil” (named for its fiery, unpleasant nature), “rumbullion” (a Devonshire slang word for a great uproar or brawl), and eventually just “rum.”

Rum, Slavery & the Triangular Trade

As rum production increased, it became a central element in the Atlantic economy. In what became known as the Triangular Trade, molasses was shipped from the Caribbean to New England, where it was distilled into rum. The rum was then traded for slaves in West Africa, who were transported back to the Caribbean to work the sugar plantations.

The Spread of Rum Culture

While its roots were in the Caribbean, rum culture spread rapidly across the colonial world. In North America, rum was often preferred over European brandies. Sailors in the British navy received daily rum rations, a practice that will be explored in greater detail in Part II. In taverns from Boston to Bridgetown, rum fuelled political discussion, rebellion, and everyday life.

Even early explorers and naturalists took note. While Thomas Cook (the Victorian-era travel pioneer) is often confused with Captain James Cook, it was the latter whose voyages in the 18th century made rum a staple provisioning item. Rum helped fight scurvy, lifted morale, and became a key part of maritime life.

A Spirit Forged in Fire

Rum is not just a byproduct of sugar; it is the story of empire in a bottle. Born of exploitation and ingenuity, rum represents both the horrors of colonialism and the resilience of culture. As techniques improved, so did the spirit’s quality. From its rough “kill-devil” beginnings, rum would evolve into a nuanced and celebrated drink, rich in regional identity and global legacy.

In Part II, we explore how rum took on new meaning in the English-speaking world, from naval traditions to American rebellion. The journey from molasses to revolution continues.

Jeffreys Bay May 2025

Here goes your text … Select any part of your text to access the formatting toolbar.

The History of Rum – Part 2: The Colonial Spirit

Rum in the English-Speaking World

In the vast colonial tapestry of the British Empire, few spirits came to define an era quite like rum. More than just a drink, rum was currency, medicine, ration, and morale-booster across centuries of maritime domination and colonial expansion. While Part 1 traced rum’s origins in the Caribbean and its early global diffusion, Part 2 dives into its entrenchment within the English-speaking world, from the docks of London to the holds of Royal Navy ships, and from sugar plantations to the heart of British identity abroad.

Rum and the Royal Navy: A Bond Forged at Sea

No examination of rum in the English-speaking world can begin without acknowledging the Royal Navy’s long, storied relationship with the spirit. The iconic “rum ration,” commonly known as the “tot,” became institutionalized in 1655 following the English capture of Jamaica from the Spanish. With wine and brandy supplies disrupted and beer unsuitable for long voyages, the Navy turned to the abundant, cheap, and high-proof local sugar spirit—rum.

By the 18th century, the rum ration had become a deeply embedded part of naval life. However, raw rum was potent and often destructive to discipline. To counter this, Admiral Edward Vernon ordered in 1740 that rum be diluted with water and sometimes lime juice. His nickname, “Old Grog,” given for his grogram cloak, gave rise to the drink’s new name: grog. This measure also inadvertently helped fight scurvy, laying the foundation for the Navy’s dual reputation for hard discipline and hard drinking.

Yet as naval technology advanced and global tensions escalated in the 20th century, rum’s place in modern military life came under scrutiny. Submarines, especially those equipped with nuclear weapons, represented a new frontier of warfare where clear thinking, constant readiness, and sober judgment were paramount. The symbolic end came when it was officially determined that serving rum daily aboard a submarine capable of launching nuclear missiles was a risk too grave. In 1970, the Royal Navy formally ended the daily rum ration, an event mourned as “Black Tot Day”—a final toast to a centuries-old tradition.

Blending Tradition: The Art of Navy Rum

While many nations produced rum, the English-speaking world distinguished itself with a particular approach to blending. Navy rum was not tied to a single distillery or island; instead, it was a blend of rums from various British colonies, including Jamaica, Guyana (formerly British Guiana), and Barbados. This created a deep, rich, full-bodied style, robust enough to satisfy sailors who were paid partly in rum.

The British Royal Navy blend became iconic, defined by its dark colour, strong molasses character, and a powerful punch—typically overproof. Brands like Pusser’s Rum preserve this blending tradition today, offering modern consumers a taste of the seafaring past.

In time, other English-speaking regions developed their own styles:

- Jamaican rums became known for their funky esters and pot still richness.

- Barbadian rums favoured balance and elegance, with column still influence.

- Trinidad developed lighter, cleaner rums with increasing industrial standardization.

- Guyana, using the legendary wooden stills of Demerara Distillers, crafted uniquely dark, smoky profiles.

Rum and Empire: Commerce, Control, and Culture

In colonial America, especially New England, rum took on a life of its own. Molasses imported from the West Indies fed a booming distilling industry in places like Rhode Island and Massachusetts. Rum became the currency of the transatlantic triangle trade, exchanged for slaves and other goods in West Africa. Some historians suggest that by the mid-18th century, New England rum was so dominant that it rivalled British exports.

Rum was also at the heart of tax disputes and revolts. The Molasses Act of 1733, and its later successor the Sugar Act, were designed to protect British West Indian planters by taxing molasses from non-British colonies. These unpopular acts helped ferment unrest in the American colonies, indirectly contributing to revolutionary sentiment.

In the Caribbean, the legacy was even more entwined with empire, forced labour, and extraction. Sugar plantations, reliant on enslaved African labour, produced the molasses that fed the stills. While the English-speaking world refined rum into an art and an identity, the human cost of its production lingered heavily.

The Cultural Spirit of the Anglosphere

Even after the days of colonial conquest and empire waned, rum remained a cultural symbol in English-speaking societies. It became embedded in tropical tourism, pirate folklore, naval reenactments, and craft cocktail revivals.

Today, the blending legacy of English-style rum lives on in both traditional and modern distilleries. Craft producers in places like the UK, the US, Australia, and South Africa (including distilleries like Ferreira Post) are reviving old techniques while experimenting with local innovation. The English-speaking world’s influence on rum was not just about empire, but about adaptation, refinement, and endurance.

Looking Ahead

In Part 3, we will turn our attention to the Latin legacies of rum: the French, Spanish, and Portuguese-speaking worlds. We will explore how different colonial approaches, regulations, and palates created distinct rum traditions like rhum Agricole, ron añejo, and cachaça—and how revolution, identity, and terroir shaped them.

Jeffreys Bay

May 2025

Part 3: The Latin Legacy: Rum’s Origins in the Spanish and Portuguese Worlds

When most people think of rum, they picture sun-drenched Caribbean islands or sea-faring pirates swigging grog. However, the deeper history of rum stretches back through colonial ambition, cultural exchange, and agricultural transformation — with Latin Europe playing a pivotal and often overlooked role. While the British Caribbean colonies helped popularise rum and shape its industrial identity, it was in the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking worlds where the foundations of rum were truly laid.

The Iberian Sugar Trail

To understand the Latin origins of rum, we must begin with sugar — the crop that made the spirit possible. Long before sugarcane fields covered the Caribbean, this tropical plant was cultivated in Southeast Asia and then introduced to the Mediterranean by returning Crusaders. By the 15th century, the Portuguese and Spanish had brought sugarcane to their island colonies off the African coast, such as Madeira, the Azores, and the Canary Islands. These early experiments in sugar cultivation became the prototypes for the sprawling plantation economies later established in the Americas.

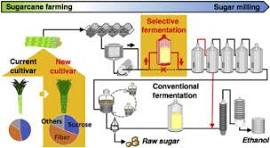

Integrated Sugar Mill

The Portuguese, in particular, were instrumental in refining sugar production techniques. They developed the “engenho” system in Brazil — integrated sugar mills where sugarcane was crushed, boiled, crystallised, and byproducts like molasses collected. As sugar was processed, the leftover molasses began to ferment in the tropical heat. Early colonial sources in Brazil refer to a strong, fiery drink made from these residues: “cachaça”.

Cachaça – The Proto-Rum

Cachaça, still a popular spirit in Brazil today, is often considered the first true rum. It appeared in the early 1500s, shortly after the Portuguese began cultivating sugarcane on a large scale. The spirit was produced by fermenting and distilling fresh sugarcane juice or molasses, a practice that likely drew on Moorish and European distillation traditions but adapted them to the New World context.

The Portuguese Crown regulated cachaça by the 17th century, treating it as both a valuable export and a colonial currency. Enslaved Africans were sometimes paid in cachaça, and it became deeply embedded in the social fabric of colonial Brazil. Though not yet called “rum,” cachaça was part of the same family of cane spirits — and arguably the earliest.

The Spanish Colonies and the Rise of Aguardiente de Caña

In the Spanish-speaking Americas, a similar story unfolded. As Spain colonised vast swaths of the Caribbean and mainland Latin America, sugarcane plantations sprang up across Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola (now the Dominican Republic), and Venezuela. These plantations soon produced an abundance of molasses, leading to the development of “aguardiente de caña” — literally “fiery water from cane.”

Unlike the industrial-scale rum operations of the British colonies, aguardiente was often made in smaller batches for local consumption. The Spanish colonies were slower to industrialise sugar refining and distilling, in part because their economies were more diversified and also because the Spanish Crown initially restricted private distillation to maintain control over alcohol taxation and imports from Spain.

Nevertheless, aguardiente grew in popularity among slaves, indigenous peoples, soldiers, and settlers alike. Over time, it developed regional identities: in Venezuela, it became known as “ron”; in the Andes, variants like aguardiente de panela (made from solid cane juice) emerged. Although these early Latin rums were often rustic, they laid the groundwork for some of the world’s most celebrated rums today — such as Ron Diplomático (Venezuela) or Ron Matusalem (Cuba/Dominican Republic).

Distilling Meets Latin Culture

What distinguishes the Latin rum tradition is not only its historical timing but also its cultural texture. In the Latin world, rum was not merely a commodity or naval ration — it was woven into religious festivals, folk medicine, and local customs. In Cuba, for example, rum became an essential component of Santería rituals. In Brazil, cachaça featured prominently in Carnival and regional feasts.

Moreover, while British rums tended to focus on bold, heavy pot-still styles, Latin producers often preferred smoother, column-distilled spirits. This distinction persists today in the lighter, drier rums of Puerto Rico and Cuba versus the richer, funkier styles of Jamaica or Barbados. The Latin legacy of rum is one of finesse, adaptability, and local flavour.

From Aguardiente to Global Rum

By the late 18th and 19th centuries, “ron” (Spanish) and “rum” (English) began to merge in global perception. Improved distilling methods, international trade, and colonial competition brought rums from all over the Americas into contact. The lines between Anglo and Latin rum styles began to blur — especially as independent republics replaced colonial empires, and distilleries modernised.

Yet, the Latin contribution to rum’s story remains vital. It was the Portuguese and Spanish who first planted the cane, first distilled the spirit, and first gave it cultural meaning. Today, as connoisseurs explore the nuanced world of craft rum, many are rediscovering the elegance of Latin-styled rums — whether it’s a solera-aged Cuban añejo or a small-batch Brazilian cachaça.

In Conclusion

While British colonies may have popularised rum on the global stage, the Latin world deserves recognition for birthing the spirit itself. From the sugar fields of Brazil to the distilleries of Cuba and Venezuela, the Latin legacy of rum is one of deep roots, cultural richness, and enduring influence. For those of us in the craft distilling movement — like Ferreira Post Distilleries in Jeffreys Bay — it’s a heritage worth celebrating and building upon. Next time we will endeavour to look at how rum is enjoyed globally.

Jeffreys Bay June 2025

Part 4: Rum Without Borders: How the World Enjoys Rum

Few spirits have travelled as far or as freely as rum. Born from sugarcane byproducts and raised in the tropics, rum has transcended its Caribbean and Latin roots to become a global staple. Today, rum is not only a spirit of sailors and pirates—it is a cultural symbol enjoyed in countless ways across continents. From tiki bars in California to street-side kiosks in Manila, rum is as much about how it’s enjoyed as it is about how it’s made.

Tiki Bar – False Idol, San Diego

A Drink of Many Traditions

Each region puts its own cultural stamp on rum consumption. In the Caribbean and Latin America—the heartlands of rum—locals often drink it neat or over ice to appreciate the craft of aging and blending. In Cuba, a glass of añejo (aged rum) is a mark of hospitality. In Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, sipping rum is woven into daily life, with bottles like Brugal or Don Q taking centre stage at family gatherings and festivals.

Meanwhile, in places like Barbados and Jamaica, rum is a source of national pride, often enjoyed with simple mixers such as coconut water, ginger beer, or soda, depending on the occasion. It’s not unusual for friends to gather and “lime”—Caribbean slang for relaxing together—with a bottle of local rum and casual conversation.

The Rise of Rum Cocktails

Globally, rum is perhaps best known for its versatility in cocktails. The Daiquiri, Mojito, Piña Colada, and Mai Tai are just a few examples of classic drinks where rum is the hero. These cocktails helped export rum culture far beyond the tropics, introducing new generations to rum’s rich, fruity, and sometimes spicy profile.

Mai Tai

In the United States, post-Prohibition tiki culture of the 1940s and 50s glamorized rum as the drink of exotic escapism. Tiki bars spread across the nation, pairing elaborate rum cocktails with Polynesian-inspired decor. Even today, cities like San Francisco, New York, and London host some of the world’s top rum cocktail bars.

In modern mixology, premium rums are increasingly treated like fine whiskeys—served in snifters or rocks glasses to appreciate their depth, complexity, and terroir. Craft cocktail enthusiasts often reach for small-batch rums for bespoke drinks or minimalist serves that highlight the spirit’s character.

Rum and Coke: The Global Default

For millions of people, however, rum is synonymous with a single serve: Rum and Coke. Known in Cuba as the Cuba Libre, this simple mix of rum, Coca-Cola, and a squeeze of lime has become one of the world’s most popular highball drinks.

Cuba Libra

Coca-Cola itself is a complex beverage, made with spices, citrus oils, vanilla, and caramel—a flavour matrix that complements rum beautifully. In many ways, the rise of Coca-Cola helped rum spread globally. From Africa to Asia, wherever Coke became available, rum often followed. This cultural partnership between rum and cola is so powerful that in many parts of the world, ordering a “rum” at the bar silently assumes a mixer—Coke by default.

In Part 5 we will explore Coke in more depth, as Coke’s complexity and heritage are a story of their own.

India: Whiskey or Rum?

One of the lesser-known global quirks of rum consumption happens in India, now the world’s largest consumer of “whiskey.” However, much of what is labelled and sold as Indian whiskey is technically rum—or at least rum-like. Many Indian whiskies are produced using molasses spirit rather than grain distillate, making them closer to rum by international standards. This is partly due to India’s sugarcane industry, where molasses is abundant and cheap, and partly due to local laws that allow for molasses-based spirits to be marketed as whisky.

Brands like Old Monk, a dark rum with a cult following in India, blur the lines between rum and whiskey culture even further. Old Monk is consumed by millions, often in the same way whiskey is drunk elsewhere: with water, soda, or on the rocks.

This curious crossover highlights a broader truth—rum’s identity is often shaped more by tradition and marketing than by strict technical definitions.

Asia and the Pacific

In the Philippines, Tanduay is one of the world’s largest rum brands, consumed both as a mixer and neat. In Thailand, SangSom—a sugarcane-based spirit often called a “rum” in casual conversation—has long been a national favourite, served with soda and ice at beach parties and bars. In Australia and New Zealand, Bundaberg Rum is almost a cultural icon, affectionately known as “Bundy” and enjoyed in everything from pre-mixed cans to celebratory shots.

Rum in Thai Land

A Spirit for All People

Whether it’s sipped neat, mixed with Coke, blended into cocktails, or passed off as whiskey, rum has an unmatched global footprint. It crosses cultural and class boundaries, equally at home in street festivals, five-star hotels, beach bars, and backyard braais. Rum’s story is one of adaptation and integration—a liquid passport that continues to evolve as it travels.

As the world keeps sipping, stirring, and celebrating with rum, one thing is clear: there’s no wrong way to enjoy it.

Jeffreys Bay July 2025

- From soda fountain to global icon: The story of Coca-Cola, and the future of craft rum in South Africa

Few beverages in the world can claim the universal recognition and cultural impact of Coca-Cola. Born in the American South, refined over the decades, and today consumed in virtually every country, Coke has become more than just a drink — it’s a symbol, a mixer, and a taste memory shared by billions.

Coca-Cola headquarters in Atlanta

A Sweet Beginning in Atlanta

The Coca-Cola story starts in 1886 with Dr. John Stith Pemberton, a pharmacist in Atlanta, Georgia. Seeking a medicinal tonic to help with headaches and fatigue, Pemberton created a syrup made from a combination of kola nut extract (a source of caffeine), coca leaf extract, and a carefully guarded blend of flavouring oils and spices — the now-legendary “Merchandise 7X.” He sold it at Jacobs’ Pharmacy for five cents a glass, mixed with carbonated water. The drink was an instant hit.

Pemberton’s bookkeeper, Frank M. Robinson, coined the name “Coca-Cola” and designed the flowing Spencerian script logo, still used today. After Pemberton’s death, businessman Asa Candler acquired full rights to the drink and aggressively marketed it nationwide, laying the foundation for a beverage empire.

From Local Treat to Global Phenomenon

In the early 20th century, Coca-Cola expanded rapidly, thanks to innovative bottling and franchising. The famous contour glass bottle, introduced in 1915, set the brand apart visually. By World War II, Coke was so tied to American identity that the U.S. government arranged for servicemen to have access to it wherever they were deployed — a move that not only boosted morale but also cemented the drink’s global reach.

By the late 20th century, Coca-Cola had transcended borders, cultures, and political systems. It became a symbol of Western culture in the Cold War era and one of the first truly global consumer products.

How Coca-Cola is Made

The core of Coca-Cola’s production process is remarkably consistent worldwide. Local bottling plants receive concentrated syrup from The Coca-Cola Company and mix it with carbonated water and sweetener — either cane sugar, beet sugar, or high-fructose corn syrup, depending on regional preferences and regulations.

The magic, however, lies in that secret flavour blend. While the exact recipe remains closely guarded, it’s known to include citrus oils, cinnamon, nutmeg, and other aromatic components. Coca-Cola’s formula is also carefully balanced for mouthfeel and carbonation level — two factors critical to its trademark “bite.”

Coke Around the World

Though Coca-Cola maintains a consistent core taste, subtle variations exist from country to country. In South Africa, cane sugar gives it a cleaner, more rounded sweetness compared to the corn syrup-based Coke found in parts of the U.S. In Mexico, the glass-bottled version sweetened with pure sugar has achieved cult status among aficionados. In Japan, Coca-Cola has introduced seasonal and novelty flavours, from peach to coffee-infused Coke.

Its role also changes culturally. In the Philippines, Coke is often enjoyed at breakfast; in Latin America, it’s a staple at family gatherings; in the U.S., it’s part of the fast-food ritual. And of course, in much of the world, Coke is a classic mixer for spirits — especially rum.

The Timeless Rum and Coke

Rum and Coke may be one of the simplest mixed drinks in the world, but it’s also one of the most enduring. Its roots trace back to the early 1900s, when American soldiers stationed in Cuba combined the island’s rum with Coca-Cola and toasted “¡Por Cuba Libre!” — for a free Cuba. Since then, the combination of caramel-toned sweetness from Coke and the tropical, often vanilla-tinged depth of rum has been a match made in cocktail heaven.

From Caribbean beaches to South African braais, the pairing offers an easy, refreshing way to enjoy rum without masking its character.

Craft Rum’s Moment in South Africa

South Africa’s craft beverage sector has undergone a quiet revolution in the past decade, driven largely by the gin boom. Small distilleries across the country showcased how local botanicals, artisanal methods, and storytelling could capture the imagination — and the wallets — of consumers. This success has set the stage for the next big wave: craft rum.

While rum has a long history tied to sugarcane production in Africa, it has often been overshadowed locally by whisky and brandy. But things are changing. Distillers are experimenting with high-quality molasses, exploring barrel ageing in the diverse South African climate, and introducing flavoured and spiced rums that rival their global counterparts. There’s also a growing consumer appetite for authenticity — spirits made with traceable ingredients, distilled with care, and offering a sense of place.

The potential is enormous. South Africa’s coastal terroirs offer unique maturation conditions, where ocean breezes, warm days, and cool nights work their magic on ageing rum. Add to that a tourism market eager for tasting room experiences, cocktail culture’s embrace of rum’s versatility, and a consumer base already trained to seek out premium craft spirits thanks to gin — and you have fertile ground for a rum renaissance.

In short, if the last decade belonged to craft gin in South Africa, the next may well belong to craft rum. And when it does, chances are good that more than a few of those rums will be enjoyed topped up with ice, fizz, and the unmistakable caramel sparkle of a Coca-Cola.

Jeffreys Bay Aug 25