Blog

Rum history

Part 2: The Colonial SpiritPart 3: The Latin LegacyThe History of Rum, Part I: The Origins of Rum – Sugar, Slavery & Spirit

Part I of a Trilogy:

- The History of Rum in General and Development

- The Colonial Spirit: Rum in the English-Speaking World

- Rum and Revolution: French, Spanish & Portuguese Contributions

Rum’s history is inextricably linked to the great tides of global exploration, colonization, slavery, and trade. While today it’s seen as a tropical indulgence, its origins are rooted in some of the most transformative and turbulent chapters of human history. Before we explore how rum shaped the colonial and revolutionary worlds in later parts of this series, we begin here: with the birth of rum itself, and the sweeping story of sugar, slavery, and spirit.

From Grass to Gold: The Global Journey of Sugarcane

Sugarcane, a towering tropical grass, originated in Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. As early as 500 BCE, people in India had learned to extract and crystallize sugar. The knowledge moved westward via trade and conquest, and by the 7th century, Arab traders had introduced sugar cultivation to Persia and North Africa. As Europe emerged from the medieval period, returning Crusaders developed a taste for the sweet substance — and a hunger for more.

Sugarcane was later brought to the Iberian-controlled islands of Madeira and the Canaries, where plantation agriculture first took root in the 15th century. These islands became crucial testing grounds for the model of intensive sugar cultivation that would soon be exported across the Atlantic.

Columbus, Conquest & Cane

In 1493, on his second voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus brought sugarcane cuttings from the Canary Islands to Hispaniola (modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic). The Caribbean’s hot, humid climate and rich volcanic soils proved ideal for growing cane. What followed was an explosive expansion of sugar production across the region — and the beginning of what some would call the “Sugar Revolution.”

By the 16th century, European nations realized the potential of sugar as a luxury export. The Caribbean soon transformed into a network of plantations, powered by the brutal labour of enslaved Africans forcibly transported via the transatlantic slave trade.

Molasses and the Invention of Rum

Sugar refining produces a thick, dark syrup as a byproduct: molasses. Initially discarded or fed to animals, molasses began to ferment naturally in the heat of the tropics. Enslaved workers and colonists soon discovered that this fermented substance could be distilled into a potent, intoxicating drink.

By the early 17th century, rum distillation had taken hold in sugar-producing colonies like Barbados and Martinique. The earliest recorded terms for this rough spirit included “kill-devil” (named for its fiery, unpleasant nature), “rumbullion” (a Devonshire slang word for a great uproar or brawl), and eventually just “rum.”

Rum, Slavery & the Triangular Trade

As rum production increased, it became a central element in the Atlantic economy. In what became known as the Triangular Trade, molasses was shipped from the Caribbean to New England, where it was distilled into rum. The rum was then traded for slaves in West Africa, who were transported back to the Caribbean to work the sugar plantations.

The Spread of Rum Culture

While its roots were in the Caribbean, rum culture spread rapidly across the colonial world. In North America, rum was often preferred over European brandies. Sailors in the British navy received daily rum rations, a practice that will be explored in greater detail in Part II. In taverns from Boston to Bridgetown, rum fuelled political discussion, rebellion, and everyday life.

Even early explorers and naturalists took note. While Thomas Cook (the Victorian-era travel pioneer) is often confused with Captain James Cook, it was the latter whose voyages in the 18th century made rum a staple provisioning item. Rum helped fight scurvy, lifted morale, and became a key part of maritime life.

A Spirit Forged in Fire

Rum is not just a byproduct of sugar; it is the story of empire in a bottle. Born of exploitation and ingenuity, rum represents both the horrors of colonialism and the resilience of culture. As techniques improved, so did the spirit’s quality. From its rough “kill-devil” beginnings, rum would evolve into a nuanced and celebrated drink, rich in regional identity and global legacy.

In Part II, we explore how rum took on new meaning in the English-speaking world, from naval traditions to American rebellion. The journey from molasses to revolution continues.

Jeffreys Bay

May 2025

The History of Rum – Part 2: The Colonial Spirit

Rum in the English-Speaking World

In the vast colonial tapestry of the British Empire, few spirits came to define an era quite like rum. More than just a drink, rum was currency, medicine, ration, and morale-booster across centuries of maritime domination and colonial expansion. While Part 1 traced rum’s origins in the Caribbean and its early global diffusion, Part 2 dives into its entrenchment within the English-speaking world, from the docks of London to the holds of Royal Navy ships, and from sugar plantations to the heart of British identity abroad.

Rum and the Royal Navy: A Bond Forged at Sea

No examination of rum in the English-speaking world can begin without acknowledging the Royal Navy’s long, storied relationship with the spirit. The iconic “rum ration,” commonly known as the “tot,” became institutionalized in 1655 following the English capture of Jamaica from the Spanish. With wine and brandy supplies disrupted and beer unsuitable for long voyages, the Navy turned to the abundant, cheap, and high-proof local sugar spirit—rum.

By the 18th century, the rum ration had become a deeply embedded part of naval life. However, raw rum was potent and often destructive to discipline. To counter this, Admiral Edward Vernon ordered in 1740 that rum be diluted with water and sometimes lime juice. His nickname, “Old Grog,” given for his grogram cloak, gave rise to the drink’s new name: grog. This measure also inadvertently helped fight scurvy, laying the foundation for the Navy’s dual reputation for hard discipline and hard drinking.

Yet as naval technology advanced and global tensions escalated in the 20th century, rum’s place in modern military life came under scrutiny. Submarines, especially those equipped with nuclear weapons, represented a new frontier of warfare where clear thinking, constant readiness, and sober judgment were paramount. The symbolic end came when it was officially determined that serving rum daily aboard a submarine capable of launching nuclear missiles was a risk too grave. In 1970, the Royal Navy formally ended the daily rum ration, an event mourned as “Black Tot Day”—a final toast to a centuries-old tradition.

Blending Tradition: The Art of Navy Rum

While many nations produced rum, the English-speaking world distinguished itself with a particular approach to blending. Navy rum was not tied to a single distillery or island; instead, it was a blend of rums from various British colonies, including Jamaica, Guyana (formerly British Guiana), and Barbados. This created a deep, rich, full-bodied style, robust enough to satisfy sailors who were paid partly in rum.

The British Royal Navy blend became iconic, defined by its dark colour, strong molasses character, and a powerful punch—typically overproof. Brands like Pusser’s Rum preserve this blending tradition today, offering modern consumers a taste of the seafaring past.

In time, other English-speaking regions developed their own styles:

- Jamaican rums became known for their funky esters and pot still richness.

- Barbadian rums favoured balance and elegance, with column still influence.

- Trinidad developed lighter, cleaner rums with increasing industrial standardization.

- Guyana, using the legendary wooden stills of Demerara Distillers, crafted uniquely dark, smoky profiles.

Rum and Empire: Commerce, Control, and Culture

In colonial America, especially New England, rum took on a life of its own. Molasses imported from the West Indies fed a booming distilling industry in places like Rhode Island and Massachusetts. Rum became the currency of the transatlantic triangle trade, exchanged for slaves and other goods in West Africa. Some historians suggest that by the mid-18th century, New England rum was so dominant that it rivalled British exports.

Rum was also at the heart of tax disputes and revolts. The Molasses Act of 1733, and its later successor the Sugar Act, were designed to protect British West Indian planters by taxing molasses from non-British colonies. These unpopular acts helped ferment unrest in the American colonies, indirectly contributing to revolutionary sentiment.

In the Caribbean, the legacy was even more entwined with empire, forced labour, and extraction. Sugar plantations, reliant on enslaved African labour, produced the molasses that fed the stills. While the English-speaking world refined rum into an art and an identity, the human cost of its production lingered heavily.

The Cultural Spirit of the Anglosphere

Even after the days of colonial conquest and empire waned, rum remained a cultural symbol in English-speaking societies. It became embedded in tropical tourism, pirate folklore, naval reenactments, and craft cocktail revivals.

Today, the blending legacy of English-style rum lives on in both traditional and modern distilleries. Craft producers in places like the UK, the US, Australia, and South Africa (including distilleries like Ferreira Post) are reviving old techniques while experimenting with local innovation. The English-speaking world’s influence on rum was not just about empire, but about adaptation, refinement, and endurance.

Looking Ahead

In Part 3, we will turn our attention to the Latin legacies of rum: the French, Spanish, and Portuguese-speaking worlds. We will explore how different colonial approaches, regulations, and palates created distinct rum traditions like rhum Agricole, ron añejo, and cachaça—and how revolution, identity, and terroir shaped them.

Jeffreys Bay

May 2025

Part 3: The Latin Legacy: Rum’s Origins in the Spanish and Portuguese Worlds

When most people think of rum, they picture sun-drenched Caribbean islands or sea-faring pirates swigging grog. However, the deeper history of rum stretches back through colonial ambition, cultural exchange, and agricultural transformation — with Latin Europe playing a pivotal and often overlooked role. While the British Caribbean colonies helped popularise rum and shape its industrial identity, it was in the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking worlds where the foundations of rum were truly laid.

The Iberian Sugar Trail

To understand the Latin origins of rum, we must begin with sugar — the crop that made the spirit possible. Long before sugarcane fields covered the Caribbean, this tropical plant was cultivated in Southeast Asia and then introduced to the Mediterranean by returning Crusaders. By the 15th century, the Portuguese and Spanish had brought sugarcane to their island colonies off the African coast, such as Madeira, the Azores, and the Canary Islands. These early experiments in sugar cultivation became the prototypes for the sprawling plantation economies later established in the Americas.

Integrated Sugar Mill

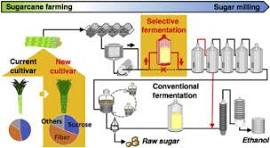

The Portuguese, in particular, were instrumental in refining sugar production techniques. They developed the “engenho” system in Brazil — integrated sugar mills where sugarcane was crushed, boiled, crystallised, and byproducts like molasses collected. As sugar was processed, the leftover molasses began to ferment in the tropical heat. Early colonial sources in Brazil refer to a strong, fiery drink made from these residues: “cachaça”.

Cachaça – The Proto-Rum

Cachaça, still a popular spirit in Brazil today, is often considered the first true rum. It appeared in the early 1500s, shortly after the Portuguese began cultivating sugarcane on a large scale. The spirit was produced by fermenting and distilling fresh sugarcane juice or molasses, a practice that likely drew on Moorish and European distillation traditions but adapted them to the New World context.

The Portuguese Crown regulated cachaça by the 17th century, treating it as both a valuable export and a colonial currency. Enslaved Africans were sometimes paid in cachaça, and it became deeply embedded in the social fabric of colonial Brazil. Though not yet called “rum,” cachaça was part of the same family of cane spirits — and arguably the earliest.

The Spanish Colonies and the Rise of Aguardiente de Caña

In the Spanish-speaking Americas, a similar story unfolded. As Spain colonised vast swaths of the Caribbean and mainland Latin America, sugarcane plantations sprang up across Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola (now the Dominican Republic), and Venezuela. These plantations soon produced an abundance of molasses, leading to the development of “aguardiente de caña” — literally “fiery water from cane.”

Unlike the industrial-scale rum operations of the British colonies, aguardiente was often made in smaller batches for local consumption. The Spanish colonies were slower to industrialise sugar refining and distilling, in part because their economies were more diversified and also because the Spanish Crown initially restricted private distillation to maintain control over alcohol taxation and imports from Spain.

Nevertheless, aguardiente grew in popularity among slaves, indigenous peoples, soldiers, and settlers alike. Over time, it developed regional identities: in Venezuela, it became known as “ron”; in the Andes, variants like aguardiente de panela (made from solid cane juice) emerged. Although these early Latin rums were often rustic, they laid the groundwork for some of the world’s most celebrated rums today — such as Ron Diplomático (Venezuela) or Ron Matusalem (Cuba/Dominican Republic).

Distilling Meets Latin Culture

What distinguishes the Latin rum tradition is not only its historical timing but also its cultural texture. In the Latin world, rum was not merely a commodity or naval ration — it was woven into religious festivals, folk medicine, and local customs. In Cuba, for example, rum became an essential component of Santería rituals. In Brazil, cachaça featured prominently in Carnival and regional feasts.

Moreover, while British rums tended to focus on bold, heavy pot-still styles, Latin producers often preferred smoother, column-distilled spirits. This distinction persists today in the lighter, drier rums of Puerto Rico and Cuba versus the richer, funkier styles of Jamaica or Barbados. The Latin legacy of rum is one of finesse, adaptability, and local flavour.

From Aguardiente to Global Rum

By the late 18th and 19th centuries, “ron” (Spanish) and “rum” (English) began to merge in global perception. Improved distilling methods, international trade, and colonial competition brought rums from all over the Americas into contact. The lines between Anglo and Latin rum styles began to blur — especially as independent republics replaced colonial empires, and distilleries modernised.

Yet, the Latin contribution to rum’s story remains vital. It was the Portuguese and Spanish who first planted the cane, first distilled the spirit, and first gave it cultural meaning. Today, as connoisseurs explore the nuanced world of craft rum, many are rediscovering the elegance of Latin-styled rums — whether it’s a solera-aged Cuban añejo or a small-batch Brazilian cachaça.

In Conclusion

While British colonies may have popularised rum on the global stage, the Latin world deserves recognition for birthing the spirit itself. From the sugar fields of Brazil to the distilleries of Cuba and Venezuela, the Latin legacy of rum is one of deep roots, cultural richness, and enduring influence. For those of us in the craft distilling movement — like Ferreira Post Distilleries in Jeffreys Bay — it’s a heritage worth celebrating and building upon. Next time we will endeavour to look at how rum is enjoyed globally.

Jeffreys Bay

June 2025